[ad_1]

It was Matt Peck’s first season of field work in the archipelago of Haida Gwaii when he found himself on a rocky island overflowing with oystercatchers, thousands of the orange-billed seabirds trilling and squawking in a riot of life.

As the researchers counted eggs on the islet off Canada’s west coast, they discovered an odd nest of twigs and grass nestled in the rocks. The team launched into a debate over which species of bird it could have housed.

“You get so excited about what it could be. But after a couple minutes, we realised what the nest was,” said Peck, a researcher with the Laskeek Bay Conservation Society. “It just hit so hard and my heart dropped.”

The nest belonged to a rat, signalling the arrival of a species that has overrun nearby islands in recent decades and killed millions of birds. For a moment, the researchers considered hurling the nest into the ocean below.

“These islands are such a beautiful, inspiring place. And some of them were so special because they’re supposed to the last places in Haida Gwaii free of invasive species. You just felt for all these birds because you knew what was coming – and it was devastating.”

The 150 islands of Haida Gwaii (“Islands of the People” in the Haida language) are under relentless attack by waves of invasive species, which threaten to upend a delicate ecosystem and erode the rich wildlife of the region.

The scourge of invasives is a global problem costing $423bn (£350bn) a year, but as local people work to fend off the intruders, the debate over their eradication raises larger questions about how ecosystems adapt over generations.

The archipelago, which the Indigenous Haida people say resembles a bear’s canine, was formed by successive volcanic upheavals. Geologists believe some of it was spared the most recent ice age, preserving several species that now exist only here: the largest black bears on the planet, and diverse subspecies of bats, ermine and otters.

But the rich genetic diversity is also increasingly being exposed to new predators, against which its millions of endemic birds, eelgrasses, berries and trees have no defence.

Long timbers covered in thick mossy lie on the ground at the edge of a forest with the shoreline seen in the background

On nearby Lyell Island, also known as Athlii Gwaii, 30,000 pairs of ancient murrelets, a species of auk, once nested on a single rocky outcrop.

But rats got to the population, devouring eggs and chicks. Now, only a handful remain – an “unfathomable” decrease, says Peck.

“People used to talk about how the sky would turn black when millions of ancient murrelets returned to their nesting grounds,” he says. “That experience is gone.”

With the threat of rain hanging overhead, Bobby Parnell eases a skiff ashore outside the town of Daajing Giids.

Their haul is pulsating inside two plastic bins: more than 1,000 European green crabs, also known as shore crabs, drawn from a single bay.

Introduced to California more than three decades ago, the invasive and ruthless crustacean has been moving northward in recent years, devastating beds of clams and eelgrass ecosystems – a key source of shelter for young fish.

In 2020, the crabs were spotted in Haida Gwaii. Each year, the haul from locals exposes the tremendous speed of their takeover. Last year, about 30,000 were pulled from the ocean. This year, with the season not yet wrapped, more than 200,000 have been trapped. “It’s devastating,” Parnell says.

The crabs have also been spotted more than a mile up the Tlell River, an important salmon spawning ground, where the crustacea could put a vital food source – and keystone species – at risk. The Council of the Haida Nation, which governs the region, has issued hundreds of contracts to cull crabs, which are then frozen and crushed into fertiliser.

“The reality is, we’re three years into the crabs being here and we haven’t yet figured it out,” says Niisii Guujaaw, a marine-management planner with the Haida Nation.

Despite the urgent, war-like mobilisation, local people worry the battle is underfunded and too late. “It feels hopeless. Sometimes when I’m out trapping crab, I look around the bay and see how large it is – and I know those crabs are everywhere,” says Tyler Bellis, a forester and former Haida Nation council member.

For many Haida, the way invasive species destroy ecosystems echoes other ways in which their lands have been made deeply vulnerable to outside forces. Smallpox outbreaks at the end of the 19th century took the population from about 30,000 to fewer than 600. And over generations, the land and waterways have been ravaged by the mechanisms of colonisation – through logging, mining, fishing and whaling.

No animal captures the devastation – and complexities – of invasive species like the blacktail deer. Introduced to Haida Gwaii as a food source by Europeans from 1878, there are now nearly 200,000 roaming the islands.

The islands are unique … so it’s really heartbreaking to see these invasive forces come in and destroy so much

Tyler Bellis, forester

They have no true predators – the bears are largely uninterested in them, having adapted to a marine diet – and so the deer overgraze the land with little resistance. Many prized medicinal plants that grow in the understory have disappeared.

The deer have a particular appetite for western red cedar saplings, known as the “tree of life” in Haida culture. As a result, on many islands, no new cedars have grown in the wild for generations.

Over recent decades, tourists have been drawn in by the forests upholstered in thick green mosses that give the illusion of rich biodiversity. But experts say these forests are in fact barren wastelands. The understory – once so thick it was difficult to traverse – has disappeared.

In 2018, Parks Canada, the government agency managing conservation areas, and the Haida community embarked on Llgaay gwii sdiihlda (“restoring balance”), using sharpshooters and culls to eradicate deer on islands in the Gwaii Haanas nature reserve.

Efforts to eradicate the deer, however, have brought mixed emotions from local people, underscoring how deer are now enmeshed within Haida Gwaii.

“When the Haida were down to only 600 people, when they were on the verge of going extinct, having a good food was invaluable,” said Bellis. “For a people that historically harvested primarily from the sea, deer have been a huge food source for the Haida, to the point that they’ve grown into a part of our culture.”

Bellis sees families bringing their children on to the land, learning to hunt for the first time. But he has also seen first-hand the destruction wrought by deer.

“And I get that not every invasive species is intentionally put here. But as Haida, who have already seen so much loss, it really stings,” he says.

“The islands are unique, and what animals got here – or have stayed here – are just so special. And so it’s really heartbreaking to see these outside invasive forces come in and destroy so much of that.”

What you can do

Support ‘Fighting for Wildlife’ by donating as little as $1 – It only takes a minute. Thank you.

Fighting for Wildlife supports approved wildlife conservation organizations, which spend at least 80 percent of the money they raise on actual fieldwork, rather than administration and fundraising. When making a donation you can designate for which type of initiative it should be used – wildlife, oceans, forests or climate.

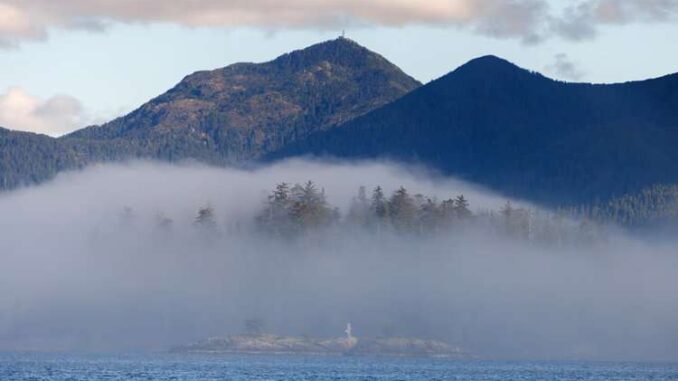

This article by Leyland Cecco in Haida Gwaii. Photographs by Cole Burston was first published by The Guardian on 23 October 2023. Lead Image: Fog shrouds trees in Gwaii Haanas national park in the Haida Gwaii archipelago, British Columbia. Geologists believe some of it was spared the last ice age, preserving species that now only exist here.

[ad_2]

Source link

Leave a Reply